VE Day - Remembering those we’ve lost.

As most of us endure a relatively stress-free "lockdown" - sitting in our PJ's, scratching our respective, collective genitalia, and stuffing cheese Quavers down our holes while watching back-to-back episodes of "only fools and horses", time marches relentlessly onwards. (although those of you familiar with any of the simpler bits of special relativity will recognise that time can also be construed as being constantly at rest while we travel at the speed of light through the universe). History tells us that seventy five years ago today, the allied armed forces in Europe accepted the formal surrender of Nazi Germany at a meeting in Berlin, after an initial surrender was agreed upon in France a day earlier by everyone except the Russians. The end of the war in Europe came to be known as VE Day (Victory in Europe). It certainly wasn't a cessation in worldwide hostilities, with the conflict still raging in the Pacific theatre, but nevertheless it marked the end of a period of grim hardship, loss, and sacrifices unparalleled by Britain in modern times. Just by chance, I stumbled on a couple of family snaps taken on VE Day in the street in which I was raised - Norbury Grove, on St. Anthony's Estate in Walker, Newcastle Upon Tyne. They both show a street party in full swing - with my dad's 3 sisters sat at the table along with scores of other women and the children of the street. It appears to be devoid of any grown men for obvious reasons. Which brings me to my main focus of today's post:

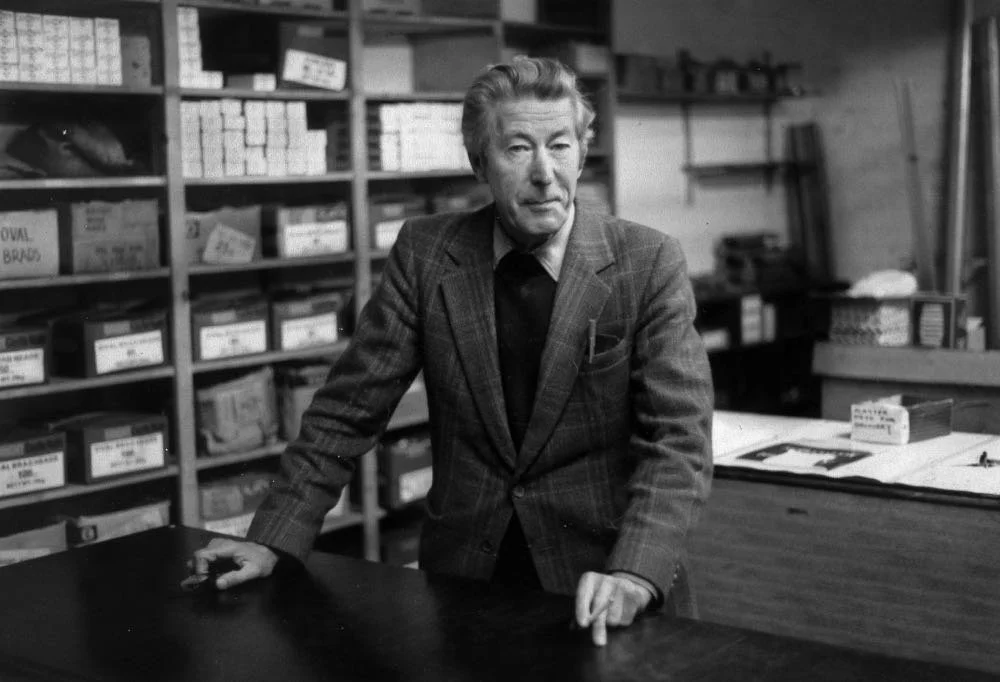

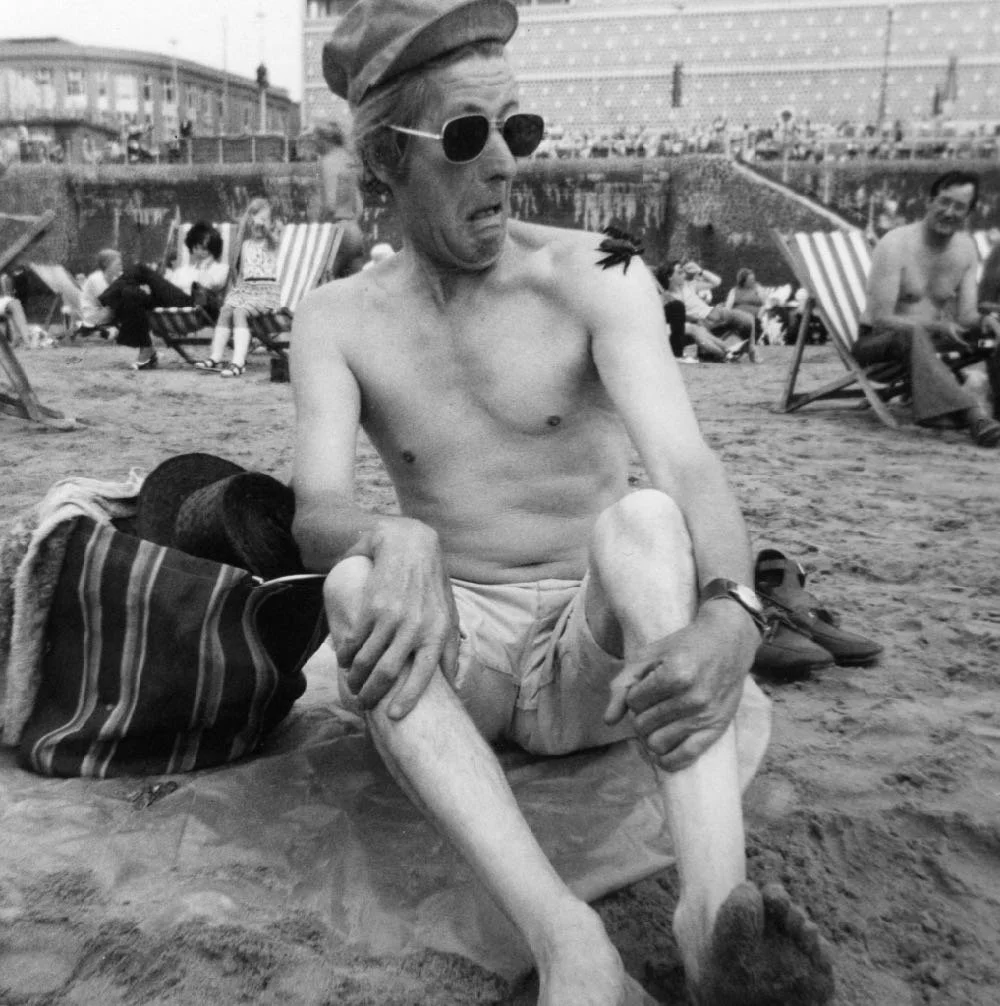

My old man (Leslie Young), one of those grown men - would have turned 100 this October. Unfortunately he passed away after waking up with abdominal pains, and deteriorating over a single day in hospital a few days before Christmas in 1996. He died with his eyes on me, and a look of concern at my distress, while a team of medics tried frantically to keep him going. His selflessness where I was concerned endured up to the last second of his life, and his influence on me was profound.

Born in 1920, he was part of an old Byker family of 5 children, living in the terraces and back-lanes of one of the most poverty-stricken working class areas of Britain. Shipbuilding, and heavy manufacturing dominated the employment opportunities of Newcastle's east end, and it was common for the menfolk of entire streets to be involved "in the yards" at Swan Hunter, or the Parsons turbine-building factory in Walker.

The chosen career path of my dad didn't conform to the norms of those boys all around him however - his love of the cinema dictated that he followed a different direction entirely, and his first job was as a reel-runner for the numerous cinemas who had to share the 16mm movie-reels, and transfer them between showings. He would unload the film with the projectionist, put it into a bag, and cycle as fast as he could to the next designated theatre in time for the scheduled start of the movie there. On occasions, he was able to sit with the projectionist and watch some of the movie if time allowed. Eventually, he was promoted to the heady role of projectionist, and could watch to his heart's content.

Just before the outbreak of WW2, he took a job as a bus conductor on the newly-introduced electric trolley buses, and remained in the job until duty called.

When the war eventually broke out, my old man was seduced by the glamour of training to be a fighter pilot. He was 19, and available for conscription, but applied to the RAF as a volunteer in an attempt to be accepted on the BCATP flying course. It took almost 2 years to train a pilot from scratch, and there were no shortage of applicants despite the huge risks. He waved goodbye to the Byker back streets, and was dispatched to Anglesey in North Wales for assessment. The results of an eye test on the first day blew away any hope of being able to ever pilot, navigate, or assist in any airborne duties. He was grounded as an RAF leading aircraftsman and allocated relevant ground-crew duties at RAF Kirkham near Blackpool. It served as a training facility for all the tradesmen involved in keeping RAF machinery and munitions in working order. Glamorous? No...essential?.....oh aye.

In 1942, the conflict in south-east Asia was in full swing, and the old man was packed up and shipped off to India via sea, and then onward to Burma to support the army and RAF offensive in the region. The sea crossing was horrific by today's standard, with access to daylight restricted to short periods in order to gradually acclimatise the skin to increasing levels of sunlight as they approached the equator. Sanitary conditions on board were primitive, and he copped for Hepatitis mid-journey, along with hundreds of others. The condition reared it's ugly head on numerous occasions from then on, including through my childhood, and eventually contributed to his death in 1996.

Burma accounted for my dad's main stint during the war. He never saw combat as such, but by all accounts, he did his fair share of jungle patrols despite being tight-lipped about it throughout my life. His enjoyment of photography and drawing resulted in an album of small prints taken by himself and others, and a selection of sketch books with depictions of film stars and movie themes. He also had a work book dropped by a Japanese counterpart somewhere in the jungle - full of hand-drawn weapon schematics and technical drawings which were way ahead of the similar books produced by British soldiers. I'd spend ages as a kid looking through them all, and eventually they were thrown away - a huge mistake.

The war ended, and my dad was retained in Burma until November 1946, before being shipped back to RAF Kirkham for the last 3 months of his service. Like me, he despised egotistic displays, and regarded the medals he'd earned as a joke. They were thrown into the sea on the journey back to Blighty. Now, I'm not in any position to ever criticise service personnel of any rank who proudly display the ribbons and medals that they accumulated throughout their time serving the country, but my dad was. He hated the nature of the marches on Remembrance Sunday, and had very little respect for those who sported scores of military regalia with such enthusiasm. His was a private war - one to remain undiscussed from all but his older brother Ernie, who would visit us every Saturday afternoon for a vigorous argument about whatever they could think up that week.

Post-war Britain must have been a strange place for the millions of men (& women) arriving back from various enclaves throughout the world. The British Empire was beginning to disintegrate, and an age of rebuilding was wholly necessary. My dad's engineering background meant that his employment opportunities were plentiful, and he began working at the Parsons factory, which was a short walk from the parental home in Norbury Grove. After some time he took up a position in an architectural ironmongery business called NF Ramsey & Co in an administration role. The company manufactured and shipped door handles, locks, and so forth to businesses worldwide. He worked for the company (which was taken over by another firm later) until he was 63, when his working life was ended due to redundancy forced upon him by the consequences of a company fraud perpetrated by a relative of the bosses.

n 1952 he met my mam - Eileen. I'll have to write my mam's biopic some other time. Needless to say, my old man courted, and fell in love with a girl from a Northumberland mining village who was a whole ten years his junior, after meeting her at some dance (as you inevitably did back then). They were married in 1955, and took over the council tenancy of the house in which my dad had lived since returning from service. I'm not sure if his parents had passed away at this time, but I suspect so - there's no sight of them in any of the wedding shots.

Starting a family proved difficult, and tragedy struck in 1964 with the birth of their first child - Alan. He sadly died within hours of being born, and with age creeping up on them, the only way that they were going to be able to become parents realistically was via adoption. That's where my story begins.

I'll not go through my childhood, as this post isn't about me. Suffice to say my Ma and Pa did exactly what any Ma and Pa should do - provide a safe, loving environment with a framework of discipline. There was none of this self-entitled bullshit about "you can be whatever you want to be", because that's just not true. My dad knew that, and encouraged me to do my best, but never pushed it too much. He was hard.....military hard, and never hugged or kissed me in an affectionate way as far as I remember. His arm would guide me gently though, and whenever something practical needed to be done - it was done. I remember Christmas Day around 1979 or 1980, when I got a Raleigh 10-speed racing bike to replace the girl's bike I'd had for bloody ages. It was icy, and I rode over to Newcastle city centre with my pals who'd also got bikes. I promptly slipped and crashed to the pavement near to Old Eldon Square, and was forced to carry the bike home as the pedal crank had bent inwards, and therefore wouldn't rotate. I'd be lost at this point as a dad, but he simply took the crank off, walked for miles looking for a cast iron, gridded drain cover to hold it, and then hammered the crank straight again. I could hear the echo of the clanking clearly - as poor folk had to endure the cacophony caused by some mental bloke hammering metal outside their house on Christmas Day!

My dad's one weakness was his over-protectiveness towards me. It became all-consuming, and instead of allowing his teenage son to develop natural confidence and independence, he took any opportunity to prevent the inevitable desire to fly the nest. I remember the conflict vividly, and although I can rationalise everything now, at the time it was suffocating. My decision to leave home and find a new life in London via University was fuelled solely by an urge to escape. Even after 5 years away, when I was forced to move back to the house I was raised in, this suffocating behaviour continued unabated. At 23 years of age, as a grown up, working man, I would regularly find the police in the house when I got in late on a Friday night after going to some nightclub with my pals - he'd report me as missing! My mam was debilitated due to a series of strokes, and this had increased his angst somewhat. When I moved in with Tina in 1992, he eventually began to accept that I was too old to be controlled.

My mam died just before Christmas in 1993 after having a final massive stroke in the house. Although it was inevitable, and a relief from the daily torture of watching a loved-one suffer, It ended my dad's enthusiasm for life completely. His last three years on the planet were peaceful, uneventful, but without any joy. Me and Tina visited regularly, and I tried to get him the odd day out, but he was becoming quite frail, and couldn't make it very far. On the day he died, he rang me very early to say he'd called an ambulance. I rushed to the hospital, and sat with him while various tests were conducted - the rectal examination proved too much, and resulted in a red-faced female junior doctor storming out of the treatment room after being sworn at repeatedly. Later on, in a bay on a ward at the RVI, as I was making plans for what to do when he was discharged, my dad's blood pressure began to drop, and within 30 minutes, and the presence of a crash team, he closed his eyes for the last time while looking directly into my soul. The death certificate cited alcoholic liver disease and the effects of Hepatitis.

He'd written a sort-of will on a bit of scrap paper while waiting for the ambulance that morning, and it was propped up on the table when we went back to his that evening. It was typical dad - pragmatic, no-nonsense, detailing instructions on how to distribute the furniture in the house, and with the closing sentence - "remember....that's life!"

And that was my old man through and through - a war veteran who always made the effort without complaint, who regarded all races and religions as equal despite the protestations and bigotry of his family and friends, who could see humour and simplicity in anything, and who ultimately passed on some of those qualities to me by his example. So, today of all days, while you might be inclined to indulge in a modicum of self-pity, try to remember the sacrifices that countless people made so that we could all live free from the absolute disgrace of the Nazi ideology, and raise a glass to those people. People like my dad.

Miss you dad.